58. Нейрофизиологические корреляты психодинамических неосознаваемых процессов Г. Шеврин (Neurophysiological Correlates of Psychodynamic Unconscious Processes. Howard Shevrin)

58. Neurophysiological Correlates of Psychodynamic Unconscious Processes. Howard Shevrin

(Paper to be presented as part of a symposium entitled Symposium on the Unconscious under the auspices cf the Georgian Academy of Sciences, Tbilisi, Georgia, USSR, 1978)

University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

In this paper I will present neurophysiological evidence supporting the psychoanalytic assumption of a dynamic unconscious. The evidence will also throw light on the nature of repression, as well as the psychoanalytic concepts of primary- and secondary-pocess thinking. Lastly, I will explore some new conceptual and research implications of these findings.

Before proceeding with the description of the method and the findings, I would like to consider briefly 1) the logical status of the unconscious as a concept, 2) the relationship between psychological and neurophysiological inquiry on the one hand and metapsychology on the other. This excursion into theory will I hope make clear what assumptions underlie my research and will assist the listener in understanding my research strategy.

In a series of little-known lectures delivered in 1944, Rapaport (Gill, 1967) proposed that the notion of a psychologically meaningful unconscious was a logical consequence, or corollary, of the basic psychoanalytic proposition that a fundamental psychic continuity existed in every individual's life. Gaps in memory, puzzling physical complaints, obsessions, phobias which persist without rhyme or reason, and even seemingly unyielding character traits, which appear to be the permanent structures of personality, are all part of a larger psychic continuity in terms of which their true meaning and development is explicable. At any given time what appears to be psychically discontinuous is really continuous if we assume that there are other psychological events which once known would vouchsafe this continuity. Rapaport stressed that "out of the logic of the situation, out of the clinical setting as the method of investigation, the concept unconscious issues without any kind of observation (1967, page 191)" or stated more emphatically and tersely, "the concept of the unconscious is indispensable by definition" (page 191). As he further stated elsewhere:

"The observation that in hypnosis and in the course of free association patients become aware of past experiences, or of relations between them, or of relations between past and present experiences, led to the assumption of the "nonconscious" survival of such experiences and the "nonconscious" existence of such relationships. But only the discovery that such nonconscious experiences and relationships are subject to rules (e.g., the pleasure principle and the mechanisms of the primary process) different from those of our conscious behavior and thinking made the above-mentioned memory phenomena (already observed by Charcot, as well as by Bernheim) into evidence for the assumption of unconscious psychological processes... (This view) rejects both consciousness and logical relations as necessary criteria of psychological processes, and thus arrives at the concept of unconscious psychological processes abiding by rules other than those of conscious processes". (1959, page 75).

One implication of these considerations is that ideas not in consciousness do not simply lapse into a dormant physiological state as Janet, Prince and James presumed. Another implication is that the very same idea, memories and percepts present in consciousness may become unconscious and thus subject to different rules of association. The unconscious is not only a crude level of content having to do with early life experiences, but is essentially a different order of organization of some of the same contents found in consciousness. A third implication is that the form and content of conscious thought may be greatly influenced by these unconscious organizations and we can detect these influences if we know what to look for.

This line of reasoning leads to the conclusion that the existence of the unconscious must be assumed in clinical work, but can only be demonstrated by methods other than the clinical method of psychoanalysis. The next question is to inquire about what other methods would lend themselves to this purpose.

The strategy of the research to be reported in this paper was thus dictated by a search for methods, which were at the same time independent of clinical method while being capable of close correlation with clinical phenomena. Not only should this approach offer a way of confirming clinical propositions which are locked into the clinical method, but should result in a better understanding of basic mental mechanisms and lead us to new conceptions of them.

Method

The method I have employed combines the psychological and clinically relevant method of subliminally activated free associations with the average evoked response, a neurophysiological means for detecting the brain's specific response to a stimulus. The subliminal stimulus I have used is noteworthy in one respect: It was designed to elicit both conceptual and clang associations by taking advantage of Freud's earliest insights into the role of language in psychopathology and dreaming - his recognition that words can serve as superficial associations, or as "bridges" for displacement and condensations. Superficial associations and verbal bridges illustrate the plasticity of primary-process ideation in the realm of language. Primary process ideation of this sort is hypothesized to be more typical of unconscious processes than of conscious processes.

Luria and Vinogradova (1959) have shown that in their exploration of what they refer to as semantic fields, adults under the influence of a mild sedative or in fear of electric shock and oligophrenic children respond with the orienting reflex to words similar in sound rather than related in meaning. The Russians ascribe this impairment of abstract thinking to organic changes, whereas our understanding of dreams and psychopathology leads us to believe that the loss of conceptual thought is an ever-lurking human failing and convenience. The abstract significance - except perhaps in cases of actual brain damage - may not be lost, but simply temporarily unavailable in experience but nevertheless active elsewhere in thought.

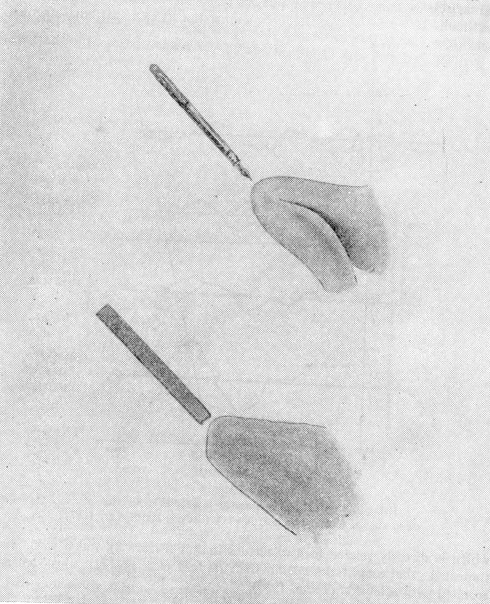

The experimental stimulus used in most of the experiments is a picture of a pen pointing at a knee (Figure 1). By tracing the conceptual associations of pen and knee, words like ink, paper, foot, leg, I am sampling rational, secondary-process thinking. But if I were to trace instead clang associations - the superficial or Wundtian external associations Freud talked about - then I would be sampling primary-process ideation. Examples of such clangs would be pennant, happen, neither, any. Finally, the two clangs can combine or condense to form a new word, penny, totally unrelated in meaning to its components. Associations to this clang condensation can be traced in the form of words such as coin, nickle, Lincoln, etc. The penny combination is another level of primary-process ideation based on the fact that the stimulus is a pictorial representation of a word, or a rebus, one of the oldest forms of writing and closely allied to dream thinking. Aside from the theoretical relevance of the stimulus, it has the technical advantage of involving no clinical judgment in scoring. Lists of associations based on normative data can be used by assistants with an error consistently less than 3%.

Figure 1. The upper figure is the experimental stimulus, a picture of a pen pointed at a leg prominent;)'' flexed at the knee. Tne lower figure is the control stimulus made up of two nonsense figures matching the experimental stimulus for configuration, shape, color and contour. The actual stimuli are in color (Shevrin and Fritzler, 1968)

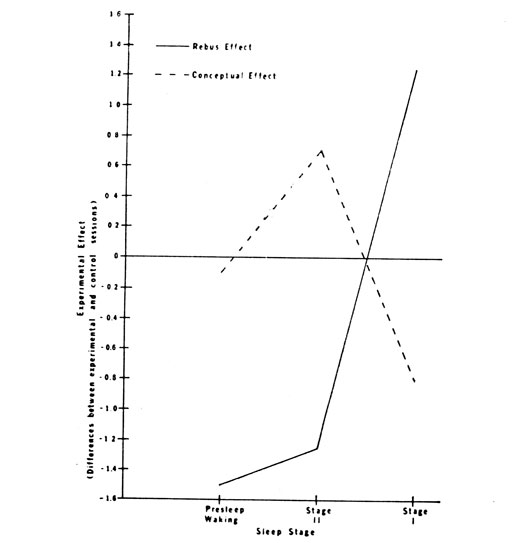

The rebus method has been used successfully in a variety of studies (Shevrin and Luborsky, 1961; Shevrin and Fisher, 1967; Stross and Shevrin, 1968). For example, in an experiment done in collaboration with Fisher (1967), we were able to show that pen and knee clang associations and penny rebus associations appeared more often in associations following stage I, rapid eye movement awakenings, than after stage II awakenings; on the other hand, pen and knee conceptual associations appeared more frequently following stage II awakenings than after stage I, rapid eye movement awakenings (Figure 2). Primary-process thought was prominent following dream arousals and secondary-process thought was prominent following one type of non-dream arousal.

Figure 2. Rebus and conceptual sub immal effects as a function of sleep stages. (Median values; N=10) (Shevrin and Fisl er, 1967)

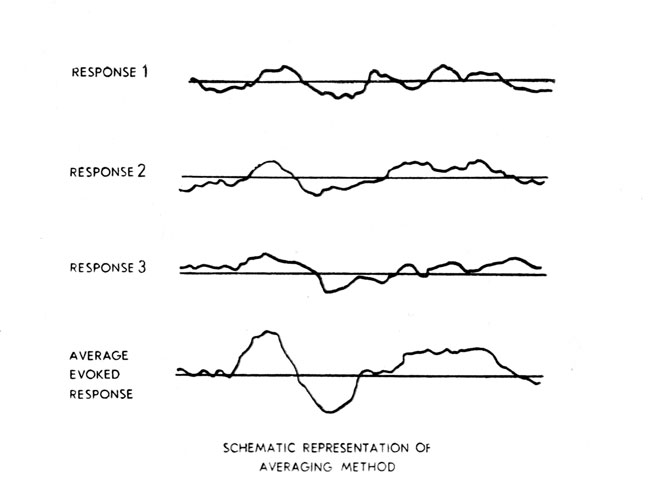

It was not, however, until the rebus method was combined with the method of average evoked responses that it became possible to detect directly brain responses to subliminal stimuli and to discover the usefulness of these waves as indicators of complex dynamic and cognitive processes. The average evoked response, or AER, is based on the sampling of short epochs of the EEG immediately following a given stimulus. Ordinarily it is difficult to detect a specific stimulus-locked response in the EEG because the EEG reflects so many other simultaneous responses to internal and external stimuli. However, by repeatedly sampling the EEG a pattern emerges which is directly related to a selected stimulus (Figure 3). Much work has indicated that amplitudes within the first 300 msec post-stimulus are associated with attention (Tecce, 1969).

Figure 3. Fach response represents a segment of the EEG for the same time epoch. It will be noted that each response appears different from the others. However, if the different segments (sampled every 4 msec.) are added algebraically then it will be seen that a consistency emerges reflected in a sizeable amplitude. The average evoked response curve shows the appearance of this amplitude. The curve is a total algebraic sum for the amplitude increment. The divided by the total number of responses to give the average

This relationship to attention was of special interest to me because it had seemed to me theoretically compelling that attentional as well as perceptual processes had to be subliminal (Shevrin, 1967). A way to test this hypothesis would be to present two matched stimuli, one of which could a priori be assumed to be more interesting than the other, and to predict that the more interesting stimulus would elicit a larger brain response.

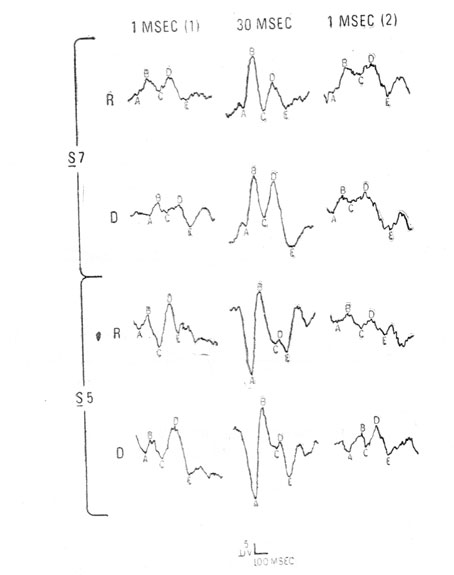

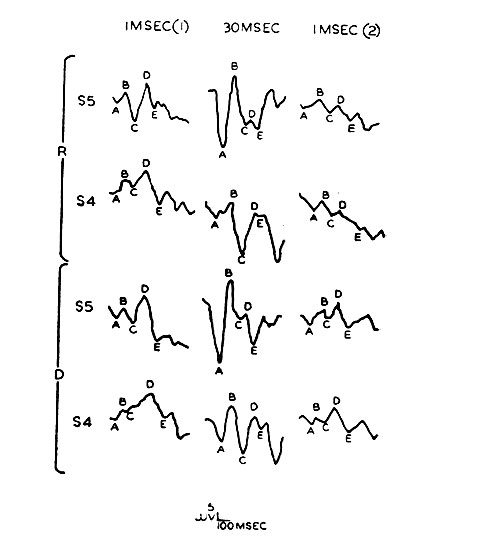

A matching pair of stimuli has been presented in a series of experiments (Figure 1). The control stimulus matches the experimental one, the pen and the knee, in a number of ways (size, configuration, color, contour) but lacks conventional meaning. In our first study we found that at one millisecond there was a consistent discrimination made between the two stimuli in favor of the rebus in the form of a larger amplitude with a latency of approximately 170 msec (Shevrin and Fritzler, 1968) (Figure 4). We have since replicated this finding twice as acceptable levels of statistical confidence (Shevrin, Smith and Hoobler, 1970; Shevrin, Smith and Fritzler, 1970).

Figure 4. Average evoked responses (From subjects 7 and 5) as recorded from frontal-occipital electrodes for each exposure condition and for each stimulus, R. and D. Average evoked responses are based on approximately 30 sweep for ear curve. Positive polarity downward (Shevrin and Fritzler, 1968)

I would like briefly to list some of the main findings the method has thus far brought to light. Following that I would like to dwell in greater detail on the nature of repression and primary-process thinking as seen from the vantage point of these findings.

Main Findings

1. A brain wave in the form of an average evoked response can be shown to discriminate between two subliminal stimuli. This discrimination is attributable to an amplitude component associated with attention which occurs at approximately 140-180 msec, post-stimulus, that is, in less than a quarter of a second.

2. Associations to the subliminal rebus stimulus are activated and can be elicited by a free association method, thus confirming that thought processes are activated by a subliminal stimulus and persist unconsciously. The subject is totally unaware of associating more of one category of words than another.

3. The conceptual, secondary-process associations (e.g., knee associations) are positively correlated with the size of the discriminating AER amplitude. The larger the AER amplitude to the rebus stimulus the more frequently will conceptual secondary-process associations be elicited. This relationship establishes a link between a truly neurophysiolog-ical event and an unconscious thought process, for the subjects can in no way be aware of this relationship.

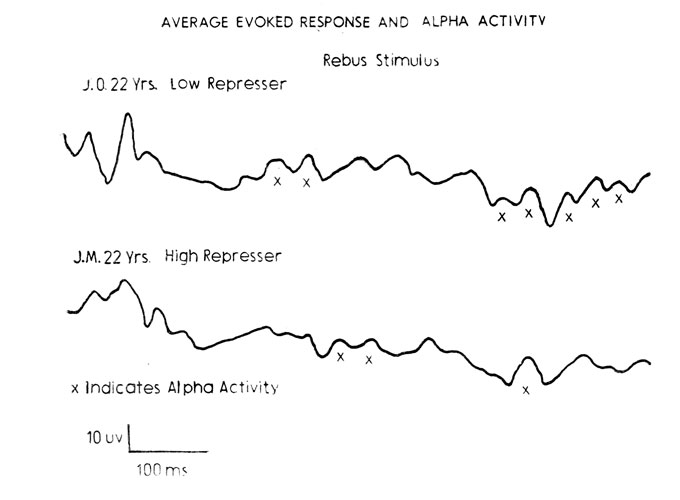

4. Primary-process associations, however, (clang and rebus words) are not correlated with this amplitude component. Rather, the incidence of primary-process associations is contingent upon the appearance of bursts of rhythmic activity in the alpha range, what neuropsychologists refer to as AER "after activity" or "ringing". It would thus seem that primary-and secondary-process thinking, as sampled by the rebus method, are coordinate with different brain processes (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The appearance of bursts of alpha in average evoked responses is illustrated by the above subjects. Wherever an x appears there is a response in the alpha range. Subject J. O. shows more alpha than J. M. He is also a low represser. His associations were characterized by a high incidence of clang and rebus associations

5. Repressiveness as rated independently on the Rorschach is negatively correlated with the magnitude of the discriminating amplitude for the subliminal stimuli: the more repressive the person is judged on the Rorschach the smaller will his AER amplitude be in response to the subliminal rebus stimulus (Figure 6). However, when the same stimulus is supraliminal there is a tendency for the high repressive person to respond with a larger amplitude to it. The highly repressive person responds differently to the same stimulus depending on whether or not it is sub- or supraliminal.

Figure 6. Average evoked response (AER) correlated for 'most' and 'least' repressive Ss. S4 is the most repressive and S5 is the least repressive S in the samp'e. The upper pairs of AER curves for the three exposure conditions are responses to stimulus R and the lower pair of curves to stimulus D. (Shevrin, Smith and Fritzler, 1969)

6. The more repressive the person the fewer stimulus-related associations of all kinds, primary- and secondary-process, he will use in his free associations.

Discussion

In the remarks to follow I would like to concentrate on the findings bearing on repression and primary-process thinking.

Repression

Repression, in Freud's formulation, is a psychic force directed against an anxiety arousing instinctual derivatives in order to keep these derivatives from becoming conscious (Freud, 1915). The term, force, is really a shorthand notation for a complex mechanism involving at least two processes:

1) the withdrawal of attention cathexis from the anxiety arousing instinctual derivative, 2) the building up of a permanent high threshold (count-er-cathexis) so that an enduring repression is established. These two processes are themselves subject to all the vicissitudes we might expect on a clinical basis. Thus, in his repression paper Freud laid stress on the shifting balance among such factors as the withdrawal of attention cathexis, strength of drive cathexis, and the role that ideationally distant and distorted derivatives play in determining access to consciousness. When repression is close to being totally effective and is a central defence of the personality we expect that a certain configuration of character traits will be observable - lack of ideational interests, emotional lability, naivete, etc In this respect we may speak of a repressive disposition. On the other hand when repression is far from fully effective, as we see in states of decompensation, then transitory phobias, anxiety states, seemingly uncharacteristic obsessional preoccupations may appear. Or, as may be true in less rigid and better compensated people, repressiveness may be highly selective and variable without triggering undue anxiety or regression. In these latter two cases we may speak of a repressive process.

What light do our findings cast on these possibilities and on the nature of the repressive mechanism underlying them? First, and crucial to our understanding of repression, is the notion that only an instinctual derivative is subject to repression. However, in what I have described we are dealing with an external, albeit subliminal, stimulus. Why should we expect a repressive force to be directed against it? The only basis on which we could expect this to happen is if the external stimulus very rapidly linked up with instinctual derivatives. The evidence we have in support of this possibility is two-fold: 1) high repressers as compared to low repressers respond to the same stimulus with a larger amplitude when it is supraliminal than when it is subliminal, suggesting that the same content for high repressers undergoes a different fate depending on whether or not it is subliminal, 2) these changes in amplitude occur only for the meaningful stimulus and not for its abstract counterpart. Thus, the repressive subject deals differently with the same meaningful stimulus depending on whether it is supraliminal o or not. These results parallel Freud's clinical observations on the role of indifferent perceptions in day-residue formation. A stimulus is more likely to lend itself to forming a day-residue if little attention has been paid to it; this condition facilitates the linking up of the indifferent perception with instinctual derivatives.

What of the postulated mechanism of repression itself? The first phase involves withdrawal of attention which takes place, in terms of the early topographic model, in the system preconscious. (I wish to leave open whether or not cathexis as a concept can best be understood as energic in nature. I am using the cathexis concept to refer solely to a phase of a process involving attention without any prejudice as to the underlyingjneurophysiological structure or mechanism involved.) There is a surprising fit with the findings if we assume that the discriminating evoked response amplitude is associated with attention, an assumption for which there is considerable evidence. This attention-amplitude is diminished in high repressive people. We also know that this amplitude is positively correlated with secondary-process associations to the subliminal stimulus, which bears out the theoretical expectation that the preconscious should be characterized by largely secondary-process functioning. So far, the theory fits well with the findings. In fact, this attention amplitude may provide an operational definition of attention cathexis. Whatever the nature of the underlying neurophysiological structure its functioning results in a measurable increment or decrement of some quantity. The mechanism itself may involve complex feedback loops such as Pribram and his co-workers (1969) have described in their research on the role of the temporal cortex in attention.

The difference in electrical potential between two parts of the brain which is measured by the average evoked response tells us that in one part of the brain a structure is in a state of heightened excitability in relation to a given stimulus. It is this state of neurophysiological excitability which may be correlated with the psychological state of attention. How this state of excitability is initiated, maintained and terminated would, on the neurological side, probably involve feedback loops of a kind described by Pribram, while on the psychological side it would involve questions of motivation, defense and reality testing. The research thus far has shown that this state of excitability: 1) occurs in response to subliminal stimuli, 2) varies with repressiveness, and 3) correlates positively with secondary-process thinking. These findings strongly imply that the mechanism of repression itself is to be found in the factors that govern the state of neuroexcitability involved in attention. Whatever decreases or increases this state with respect to particular external and internal stimuli must be a necessary part of repression. When this state achieves a stable, recurrent pattern of low excitability with respect to certain stimuli, we may speak then of a permanent anticathexis.

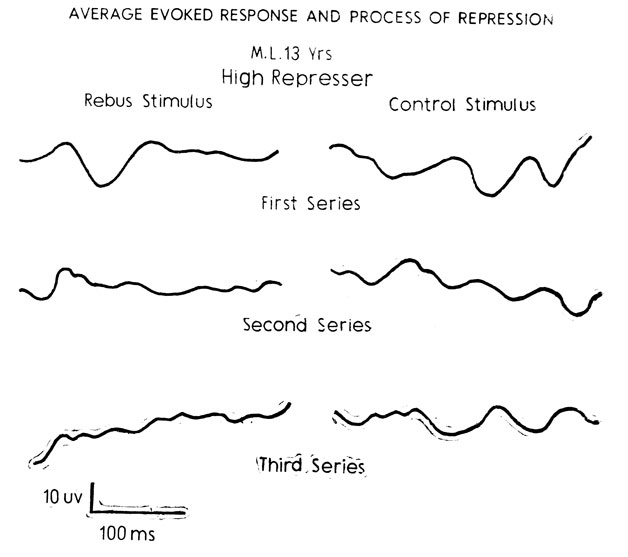

What about the second phase of the repressive"process - the building up of anti-cathexis in the form of a repressive structure? There are at least two possibilities to be considered: the repressive disposition and the repressive process models. Inferences can be drawn from these two models with respect to average evoked response activity. If the"dispositional model holds true with our subjects - young college students, male and female with no known psychiatric history - then we should expect to find that from the first evoked response to the last in the experimental series (some thirty in number), there should be a uniform flattening of the amplitude-that is, evidence of repression should be present from the very start and should be uniformly distributed throughout the series of stimulations. On the other hand, if we are dealing with a repressive process initiated with respect to a particular stimulus then we should expect to find attention to the stimulus, or monitoring of it, to occur first, which would then be followed by a flattening of amplitude as the repressive process took hold.

In a preliminary examination of high repressive subjects what we found seemed to fit the repressive process model better than the repressive disposition model. Several cases fit the monitoring-flattening sequence quite well (Figure 7). Like all high repressive 5s this S had very few stimulus-related free associations. Most of them occurred during- free associations obtained following the stimuli averaged in the first curve. The state of excitability referred to earlier diminished precipitously from the first to the second series and declined further in the third series. These neurophysiological events accompanied by diminution of stimulus-related associations may be closely related to the process of repression itself.

Figure 7. The above subject, M. L., a high represser, illustrates the initially high average evoked response to the experimental subliminal stimulus and its gradual disappearance across the series. By contrast the control stimulus shows no such diminution, thus illustrating that unconscious processes are sensitive to meaningfulness

Primary-Process Mechanisms

The direction of thought with respect to primary-process mechanisms, as with such concepts as motive and drive, has moved away from the earlier energic model toward a structural model. In the earlier model, the primary-process was conceptualized as the nature of thought, action or affect when it is impelled by the striving for immediate gratification. How this imperative condition resulted in displacements, condensations, perceptual identity and symbolizations was either slighted or described as due to special forms of energy discharge. Primary-process mechanisms were largely defined in terms of energy concepts, such as mobile cathexis. Holt (1967) has suggested that the reason for Freud's overemphasis of the energy concept at the expense of structural concepts was due to his total abandonment of neurological models after 1895. Both Gill (1963, 1967) and Holt (1967) argue forcefully for a structural conceptualization of primary-process mechanisms. Gill (1963) proposed that the concept of mobile cathexis be divorced from the primary process altogether which would then be conceptualized purely as a mode of organization activated by either drive or neutral cathexis, although he qualifies this conceptual by adding that most of the time the primary-process mode of organization is associated with drive cathexis. Holt (1967) would abandon the energy model altogether and treat the primary-process as a class of psychic structures having a specific developmental course. In neither of these writers, or in others, to my knowledge, are there any explicit hypotheses as to the formal principles on the basis of which these primary-process structures are organized or function, other than to refer to such descriptive terms as part standing for the whole, or composite figures, etc. They do, however, suggest that primary - and secondary-process mechanisms form a continuum and are not different in kind. A graded series of steps exists from the most primitive to the most sophisticated levels of psychic organization, a concept which is consistent with a hierarchical model of the psychic apparatus first proposed by Rapaport (1959) and more fully developed by Gill (1963).

How do the findings fit with both the structural views of primary-process functioning and the assumption that we are dealing with a graded series of structures9 With respect to the latter point, the data would leave some doubt. Conceptual, secondary-process associations are positively correlated with an amplitude component, while the incidence of clang-like, primary-process associations is contingent upon bursts of synchronized activity occurring approximately one second later. The same stimulus, the pen and knee, is subject to two different types of transformations occurring approximately one second apart. Even though the actual content of the associations for the primary - and secondary-process associations are superficially indistinguishable - they are all ordinary words like ankle, bone, pennant, neither, coin, cent-they have arrived in consciousness by two different routes: 1) by way of secondary-process, conceptual relationships, 2) by way of primary-process, clang relationships. It thus becomes possible to separate content from mode of organization. Once having done this we can see that these two modes of organization are associated with different brain processes, thus casting some doubt on the "continuum" hypothesis. It would have been more consistent with the continuum hypothesis if the amplitude of the attention component had been negatively correlated with the incidence of primary-process associations. This negative relationship has been found in only one of the three studies completed thus far, the study involving the fewest subjects and thus the least reliable. The non-significant relationship has been replicated. It is possible that the conceptual and clang modes of linguistic organization are at opposite ends of a continuum, in which case there should be a range of intermediate connective steps, perhaps taking the form of looser and looser associations until finally the conceptual chain is snapped and a shift to phonic relationships occurs. Yet, if this were so it would not be as useful to talk about different modes of organization. My own predilection for the sake of understanding better the nature of these different modes of organization is to start with the evident differences in the verbal and neurophysiological measures. Perhaps we might then be able to move beyond descriptive statements to some understanding of the formal organization of these different modes.

What is notable about the neurophysiological index of primary-process thinking is its synchronous character. Any organization of repetitive units may be seen as a rhythmic pattern in which the reappearance of similar units at a certain rate is of primary interest. Pribram (1969) has proposed that neurophysiological redundancy accompanies an introversive, turning away from a flexible interaction with the environment. Certainly when primary-process thinking prevails the person is less well adapted to his real environment. It might also be worthwhile to consider the alternate model - that of rhythmicity - because I believe this model may lead us to a potentially fruitful link to the concepts of instinct and drive cathexis which are theoretically closely related to the primary process.

Elsewhere, and considerably before these current findings developed (Shev-rin, 1963), I had proposed that instincts be defined as a basic rhythmic organization of brain and cognitive functioning each with its own time signature to account for their qualitative differences. At the time it seemed like a pure speculation without much empirical foundation or support from other views. I have since discovered that Kubie (1953) had proposed a related concept much earlier. More recently Lewis (1965) has developed a concept of instinct as a "continuous rhythmic activity" reflected directly in brain processes. Moreover, he postulated that each instinct must be structurally different. Lewis further proposed that the primary process because of its closeness to instinct is more likely to show temporal patterning.

I am not suggesting that there is a close fit between these speculations and the data I have described but the hiatus is pregnant with possibilities. For example, the clang-like organization of language drawn upon in the present studies is based on the redundant availability of the same sounds. This is quite different from the conceptual organization of language in which the principle is not repetition of the same element defined in terms of physical parameters, but the evocation of similar elements based on meaning. With each new conceptual association additional meanings are introduced. With each additional clang the same information is repeated. This in itself fits with a redundancy principle. But these clangs are also capable of being organized temporally in terms of rates of emission.

The rhythmic evoked response bursts accompanying clang associations may represent the actual temporal form of an instinctual process which acts as an organizing principle for cognition. Its redundancy is reflected in the repetitive appearance of certain sounds related to a given stimulus; its rate may be related to the qualitative character of the impulse. States of neural excitability alternating at a certain tempo and associated on the psychological side with states of alternating primary-process activity may be related to drive cathexis. Specifically the amplitude of these alternating states of excitability may be the neurophysiological counterpart of drive cathexis which could then vary independently of the rate, that is, the qualitative nature of each impulse.

Thus, I am hypothesizing that attention cathexis is associated with the amplitude of a linear, non-repetitive neural system functioning within approximately the first 1/4 second after a stimulus has been presented, while drive cathexis is associated with the amplitude of an oscillating, rate-sensitive neural system functioning some thousand milliseconds later. Secondly, that primary-process thinking is linked with the amount of drive cathexis, and secondary-process thinking with the amount of attention cathexis which can be translated into the terms of the previous proposition concerning the different amplitude forms. Thirdly, that repression is a process which functions at least in part through control of an attention amplitude. And lastly, that all of this may go on without any direct reflection in consciousness although these processes are detectable and measurable neurophysiologically.

Summarу

Neurophysiological evidence is offered in support of the psychoanalytic assumption of a dynamic unconscious. Experimental studies based on the average evoked response (AER) and subliminally activated conceptual and clang associations reveal that cognitive processes such as attention, perception and associations can go on unconsciously. It was also found that repression was related to a subliminal AER diminution and a decrease in stimulus-related associations. These findings appeared in the absence of any conscious awareness of changes in AER activity or association categories. Conceptual and clang associations were contingent on different features of the AER. Implications of these findings for the psychoanalytic concepts of a dynamic unconscious and for primary - and secondary-process thinking were discussed.

References

Freud, S. Repression (1915), Standard Edition, ed. Strachey, S., XIV, 141-158, Hogarth Press, London: 1957.

Gill, M. M Topography and Systems in Psychoanalytic Theory. Psychological Issues, No. 10. International Universities Press, New York: 1963.

Gill, M. M. The Primary Process, in Motives and Thought: Psychoanalytic Essays in Honor of David Rapaport, ed. Holt, R. R., Ch. 6, 258-298, Psychological Issues, Nos. 18/19, International Universities Press, New York: 1967.

Holt, R. R. The Development of the Pri тагу Process: A Structural View, in Motives and Thought: Psychoanalytic Essays in Honor of David Rapaport, ed. Holt, R.R., Ch. 8, 344-383, Psychological Issues, Nos. 18/19, International Universities Press, New York: 1967.

Kubie, L. Some implications for psychoanalysis of modern concepts of the organization of the brain. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 22, 21-68. i953.

Lewis, W. С Structural Aspects of the psychoanalytic theory of instinctual drive, affects, and time, in: Psychoanalysis and Current Biological Thought, eds. Greenfield, N. S. and Lewis, W. C, Ch. 8, 151 - 180, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison and Milwaukee: 1965.

Luria, A. R. and Vinogradova, O. S. An objective investigation of the dynamics of semantic systems. General Psychology, 50:2, 89-105, 1959.

Pribram, К. Н. Neural servosystems and the structure of personality. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 149, 30-39, 1969.

Rapaport, D. (1959) The structure of psychoanalytic theory: A systematizing. Psychological Issues, No. 6, 1960.

Rapaport, D. The scientific methodology of psychoanalysis, in Collected Papers of David Rapaport, ed. Gill, M. M., Ch. 14, 165-220, 1967.

Shevrin, H. and Luborsky, L. The rebus technique: a method for studying primary-process transformations of briefly exposed pictures. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 133, 479-488, 1961.

Shevrin H. The dreaming dreamer and the dreaming creator: a comparison of metaphor and condensation. (Paper presented at the American Orthopsychiatric Association meeting, Washington, D. C, March 9, 1963).

Shevrin, H. Perception, Registration and normal inhibition. (Paper presented to Rapaport Study Group, Stockbridge, Massachusetts, June 18, 1967).

Shevrin, H. and Fisher, C. Changes in the effects of a waking subliminal stimulus as a function of dreaming and nondreaming sleep. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 72, 362-368, 1967.

Shevrin, H. and Fritzler, D. Visual evoked response correlates of unconscious mental processes. Science, 161, 295-298, 1968.

Shevrin, H. Smith, W. H., and Fritzler, D. Repressiveness as a factor in the subliminal activation of brain and verbal responses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 149, 261-269, 1969.

Shevrin, H., Smith , W. H., and Fritzler, D. Subliminally stimulated brain and verbal responses of twins differing in repressiveness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 76, 39-46, 1970.

Shevrin, H., Smith, W. H.,and Hoobler, R. The direct measurement of unconscious mental processes: average evoked response and free association correlates of subliminal stimulation. (Paper presented at the American Psychoanalytic Association, Miami " Florida, September 6, 1970).

Stross, L. and Shevrin, H. Thought organization in hyponosis and the waking state: the effects of subliminal stimulation in different states of consciousness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 147, 272-288, 1968.

Tecce, J. Attention and evoked potentials in man, in Attention: Contemporay Theory and Analysis. David I. Mostofsky, ed., Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, 1969.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© PSYCHOLOGYLIB.RU, 2001-2021

При копировании материалов проекта обязательно ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://psychologylib.ru/ 'Библиотека по психологии'

При копировании материалов проекта обязательно ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://psychologylib.ru/ 'Библиотека по психологии'