73. Физиологические корреляты неосознаваемых психических процессов: некоторые клинические и терапевтические применения последних исследований по сну и сновидению. Ч. Фишер

73. Physiological Concomitants of Unconscious Mental Processes: Some Clinical and Therapeutic Applications of Recent Research on Sleep and Dreaming. Charles Fisher

Sleep Laboratory, Institute oi Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, USA

I will be concerned, in this paper, with some recent data on the effects of prolonged total suppression of REM sleep, the relationship of such suppression to the controversial problem of development of psychosis and other behavioral and psychic consequences. This discussion will involve the interesting problem of whether dreaming is necessary and for what. Additionally, I will present some clinical laboratory experiments relating to the treatment of night terrors, depression and narcolepsy which demonstrate that by suppressing certain sleep stages, and the states of consciousness, cognitive processes and ego states associated with them, it is possible to control or eliminate certain symptoms that arise in these states. This data illustrates how certain rational therapies are being developed based upon recent basic research findings.

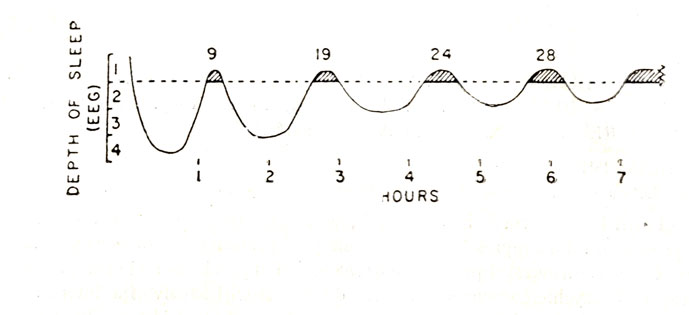

Figure 1

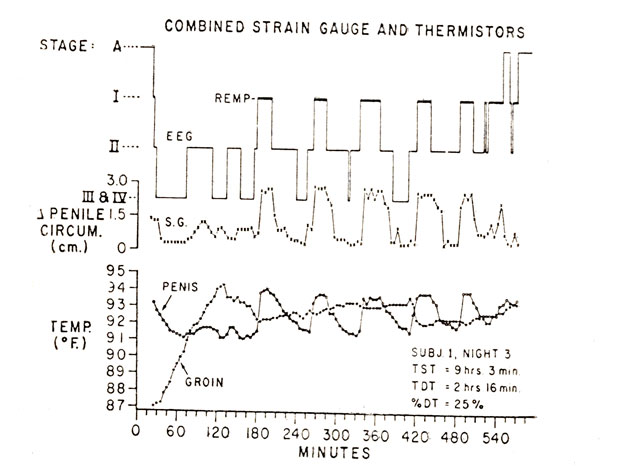

In order to refresh your memory, let me review briefly a few of the new discoveries about sleep and dreaming. There are two types of sleep which, along with waking, constitute three major organismic states. REM or dreaming sleep, which takes up about 25% of total sleep and in which we spend about one-sixteenth of our entire lives is distributed throughout the night in a 90 minute cycle (Figure 1). Non-REM, or orthodox sleep, constitutes 75% of total sleep. Stage 3-4 delta sleep predominates in the first third of the night and REM sleep in the last third. REM sleep is associated with intense activation, in both cortical and sub-cortical parts of the brain and marked activation in most physiological systems. It is also associated with drive activation as indicated by the cycle of penile erection synchronous with the REM periods (Figure 2).

Figure 2

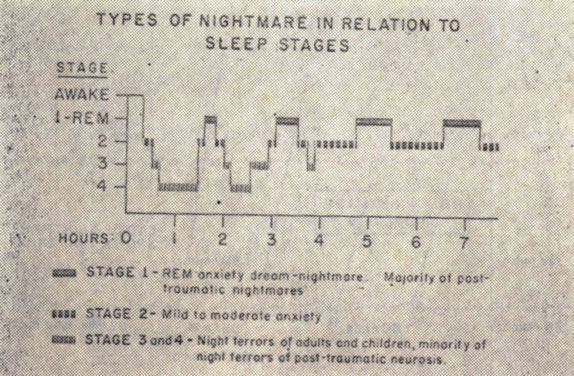

First, I want to briefly summarize the work that we and others have been doing on the major sleep disorders, namely, night terrors of children and adults, somnambulism and enuresis. It has been amply demonstrated that these disordres arise out of Stage 3-4 sleep in the early part of the night and are not associated with REM dreaming as has been traditionally assumed. We have shown that spontaneous arousals associated with anxiety of varying degrees of intensity up to panic can arise from any stage of sleep. (Figure 3). An important distinction needs to be made between the most intense, the Stage 4 night terror, which is relatively rare both in children and adults, and the much more frequent ordinary nightmare or REM anxiety dream, characterized by less intense anxiety and lower levels of autonomic discharge, motility and vocalization.

Figure 3

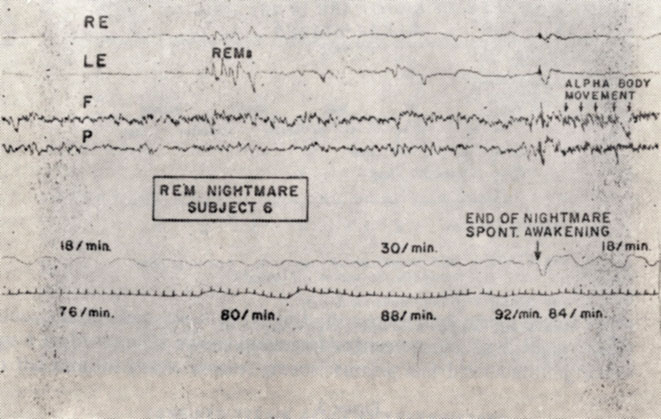

In more than two-thirds of instances, night terrors occur in the first NREM period during which nearly two-thirds of Stage 4 also occurs, as early as 15 to 30 minutes after sleep onset. In its fully developed and most severe form the Stage 4 night terror is a combination of extreme panic, fight-flight reactions in the form of gasps, moans, groans, cursing and blood-curdling piercing screams. Although triggered out of Stage 4, the episode actually takes place as part of what Broughton calls "the arousal response" characterized by a waking alpha pattern, body movement and somnambulism. The subject may be hallucinating, delusional and out of contact with the environment while he acts out the night terror which is accompanied by extreme autonomic discharge, heart rate attaining levels up to 160-170/minute within 15-30 seconds, a rate of acceleration greater than in any other human response, including severe exercise or orgasm. Respiratory rate is increased, but the most striking change is a tremendous increase in amplitude. The entire episode lasts only a minute or two, even when somnambulistic and the subject returns to sleep rapidly. Amnesia for the experience may be present, but with immediate and careful interviews, in over 50% of arousals, some kind of content is reported, usually consisting of a single brief frightening image or thought, such as the idea of an intruder in the room. In contrast, the REM nightmare arises out of an ongoing dream (Figure 4).

Figure 4

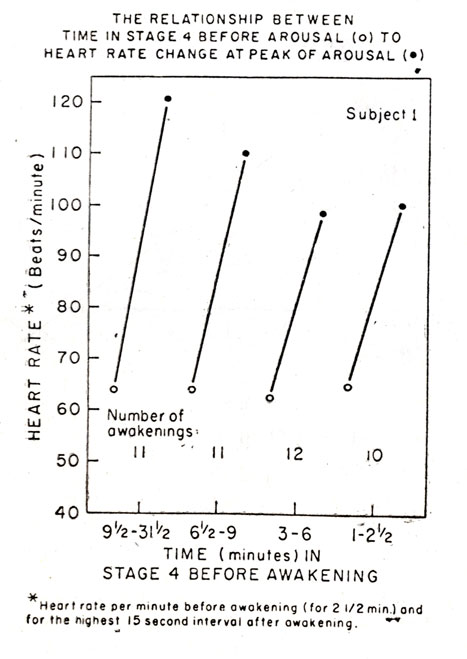

Of special interest is the physiological state just prior to the explosive, cataclysmic onset of the night terror. With rare exceptions, the night terror not only arises out of Stage 4, the most quiescent stage of sleep, but its intensity is correlated with the amount (in minutes) of this stage present just before the attack, the more Stage 4 the more severe the episode (Figure 5). That the sleep preceding onset of the night terror is quiescent is also shown by the fact that cardiorespiratory activity is normal or even slightly lower than normal. Thus, the night terror arises out of, and its occurrence is contingent upon, the presence of a specific physiological matrix, Stage 4 sleep.

Figure 5

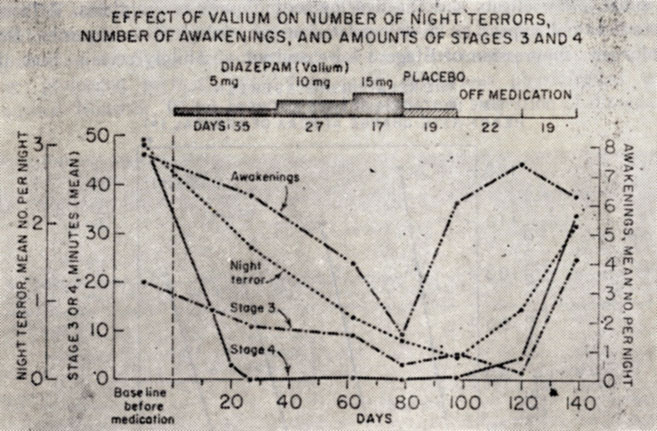

It occurred to us that if we could alter the physiological matrix out of which the night terror arises, we might be able to control the attacks. We were, however, hesitant to attempt this for two reasons: first, because removal of such a severe symptom might bring about displacement and substitute formation of a more serious nature, such as psychosis, and second, suppression of Stage 4, considered to be a necessary stage of sleep, over prolonged periods, might have some deleterious physiological consequence. However, it has been reported that chronic ingestion of diazepam, flurazepam and phenobarbital, produces marked suppression of Stage 4 without harmful effects. We decided, therefore, to test the hypothesis that administration of diazepam would bring about a prolonged suppression of Stage 4, and, in so doing, eliminate the physiological matrix out of which the night terror arises, resulting in a decrease in its incidence or even total disappearance.

Figure 6

Diazepam (Valium) in doses from 5-20 mg. was administered before bedtime to six subjects suffering from night terrors in nine experiments for periods from 26-98 days. Night terrors were reduced by an average of 80%, that is from a mean incidence of about two per night to less than one-half per night. In some instances we had 100% abolition. The decline in the amount of Stage 4 was more marked than the incidence of night terror, amounting to about 90%. Figure 6 illustrates the marked reduction in delta sleep, incidence of night terrors and of awakenings in the subject with the most severe night terrors we have studied.

Several subjects have been on Valium for more than a year and have been able to regulate the dosage so as to virtually eliminate night terrors from which they have been suffering for as long as 25 years.

As noted above, we were concerned with the possibility of displacement or substitution effects and the development of serious symptoms. Although there does not appear to be any deleterious physiological consequenes from prolonged suppression of Stage 3-4 we are not absolutely certain that diazepam administration is without harmful psychological effect. One subject did show displacements from Stage 3-4 to Stage 2, to the REM periods and finally to the daytime in the form of some rather frightening daymares. This subject turned out to have a history of convulsive seizures. Aside from this subject, however, we have not noted any harmful consequences even after very prolonged administration.

Figure 7

Aside from its connection with dreaming, the REM cycle has been alleged to have many functions but there is much about it that still remains a mystery. An important way to investigate it has, been to suppress it and to study the consequences of such suppression.

Prolonged Suppression of REM Sleep

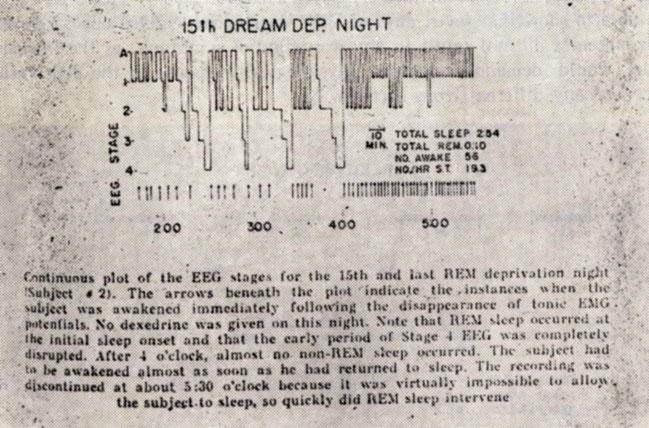

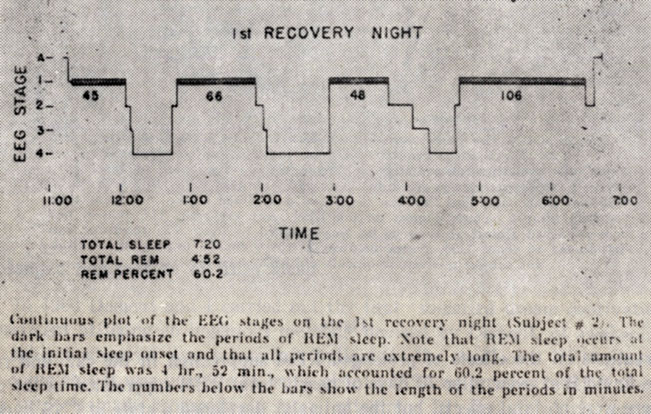

In 1960 Dement and I carried out the first so-called dream deprivation experiment utilizing an ingenious method, devised by Dement, of awakening the subject whenever eye movements indicated the onset of a REM period. By doing this it was possible to bring about a 75% suppression of REM sleep. The subjects made progressively more attempts to dream which mounted rapidly from seven on the first night to as many as 30 or more by the 5th to 7th nights. It was as though they built up a REMP pressure, that is, a pressure for REM sleep and/or dreaming which was like an irresistible force, spontaneous and obligatory. When the subjects were allowed to sleep undisturbed, they showed a marked rebound increase in REM sleep which partially compensated for the amount that had been lost during the suppression period. The longest periods of REM deprivation carried out by the waking method have been 15-16 days. Figure 7 shows such an experiment and the enormous number of awakenings that accumulated by the 15th night, rendering the experiment almost impossible. Figure 8 shows the enormous rebound increase after 15 nights of REMP suppression amounting to 60% of total sleep and the appearance of a sleep onset REM period.

Figure 8

In the first flush of enthusiasm following the dream deprivation experiments, we became convinced that REM sleep and its associated dreaming were necessary psychobiological processes, that variations, deficits or excesses, of this unique organismicrstate could befcorrelatedfwith mental disorders, and that severe and prolonged suppression of it would produce psychosis in man. These developments seemed to confirm certain psychoanalytic propositions about the importance of dreaming and the relation of dreams to psychosis, while the discovery of the erection cycle r appeared to support other propositions about the importance of sexuality and instinctual drives generally in dreaming. At the same time, Dement began to report his remarkable series of observations on the effects of prolonged REM suppression in the cat and rat. He found that even after 70 days of nearly total REM suppression in the cat there were no fatal effects, but the animals developed a state of CNS hyper-excitability during waking, characterized by the dramatic development of compulsive sexual behavior with persistent attempts by male cats to mount other males or females, awake or anesthetized, and increased eating. Rats manifested significant increases in both aggressive and sexual behavior following deprivation. In contrast to the alteration of motivational behaviors, no consistent changes were observed in basic perceptual and motor functions, learning and memory and even prolonged REM deprivation did not elicit hallucinatory behavior, contrary to expectations. The association of REM sleep and dream activity, demonstrated in humans, had led to the expectation that something analogous to dreaming would ultimately erupt into the waking state in these animals. Dement concluded that prolonged REM sleep deprivation produces generalized hyper-excitability reflecting an alteration in drive state or motivation, an increased probability that the animal will emit a stereotyped, drive-oriented response in the presence of the appropriate stimulus, or even without stimulation.

Figure 9

Although the early REM deprivation experiments in man suggested that the procedure might produce psychological disruption or even psychosis, later work threw doubt on this conclusion, and on the validity of the so-called "spill-over" or intrusion model of REM sleep in its presumed relation to mental disorder. This model proposes that whenever the pressure of REM sleep is so high that it occupies 50 to 60% of total sleep time, the REM (dream) state spillsover or intrudes into waking, producing hallucinations, delusions and psychotic symptoms. The model additionally identifies REMP pressure with drive pressure, as defined by psychoanalytic theory. However, Vogel was able to show that seven days of REM deprivation carried out on chronic schizophrenics did not result in any worsening of symptoms, as the intrusion model would demand, nor was physiological response to the deprivation procedure any different from normals.

Vogel hit on the remarkable notion that incertain conditions REM deprivation might even be helpful rather than harmful, e. g., might relieve the symptoms of depression. A number of lines of evidence led to this hypothesis, including the fact that the leading chemical anti-depressants such as Elavil, or MAO inhibitors, such as Nardil, were potent REM suppressors, that EST also suppresses REM, and the fact that prolonged REM deprivation in animals is reported to intensify several functions which are retarded in depressive illness, that is, it results in increased psychomotor and drive activity. Vogel was, in fact, able to demonstrate in a well controlled double blind study in 16 severely depressed patients, both endogenous and reactive, that periods of REM deprivation by the waking method, lasting three weeks or more, brought about marked clinical improvement.

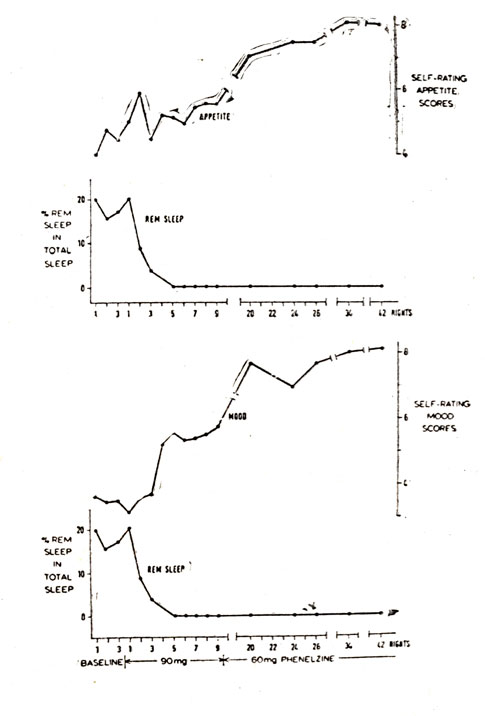

Figure 10

This surprising result has been confirmed through another approach, i. e. the total abolition of REM sleep for as long as a year through the use of the anti-depressive MAO inhibitors which cause more complete and extended REM deprivation than any other method. Wyatt et al. treated six severely, but not psychotically, depressed, anxious patients with phenelzine (Nardil) in doses up to 75 mg daily, bringing about total suppression of REM sleep for periods up to 40 days. Oswald and his co-workers have reported similar results with 15 of 18 depressed patients. They] observed that mood and appetite improvement coincided with onset of totaljabolition of REM sleep] (Figure 9) and confirmed that periods without REM sleep as long as 52 nights were without adverse effects. Thus, we are ccnfrcnied with a corrplete turnabout and paradox. Whereas it had been feared that total suppression of REM sleep might eventuate in psychosis, recent work with the MAO inhibitors and the waking method indicates that total suppression for periods as long as a year are without ill effects and, even more astonishing, large doses of Nardil have been shown to have a markedly therapeutic effect on severe anxious depressions, reactive or endogenous, improvement coinciding with the point at which total abolition of REM sleep is accomplished.

Although it is possible that the MAO inhibitors brought about the relief of depression not because of suppression of REM sleep but due to an independent biochemical action, Vogel's very similar results with REM suppression by the waking method support the notion that it is the REM suppression itself that is somehow therapeutic.

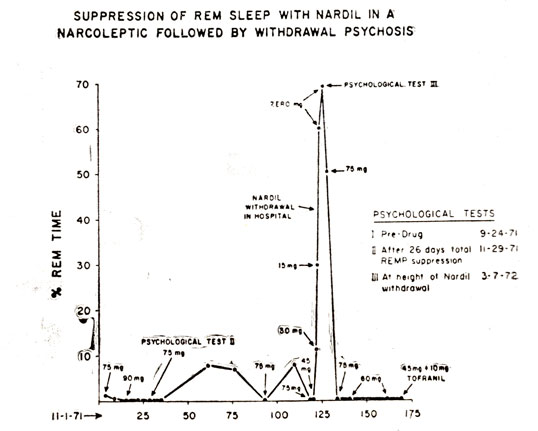

Figure 11

Another point of great interest, Wyatt and his co-workers did not systematically study dream recall but noted that following 160 nights of total REM suppression there were no reports of dreams in the morning, the inference being that there may have been a total elimination of dreaming.

I wish now to report some results of my own in confirmation of the findings of the Wyatt and Oswald groups. I have had occasion to bring about a nearly total suppression of REM sleep in two patients for periods as long as 70 nights by administering doses of Nardil up to 90 mg. Although given for therapeutic reasons, an opportunity was provided to investigate the psychological and other effects of periods of prolonged total REMP suppression and during rebound following discontinuation of the drug. In addition to recording EEG, EOG, heart and respiratory rates, we did three things not done before: (1) We made all-night recordings of penile erection, using the mercury strain gauge, (2) checked on the frequency of dreaming or other mental content during baseline, total REM suppression and the post-drug rebound, and (3) administered a battery of psychological and projective tests before, during and after total REM suppression.

Figure 12

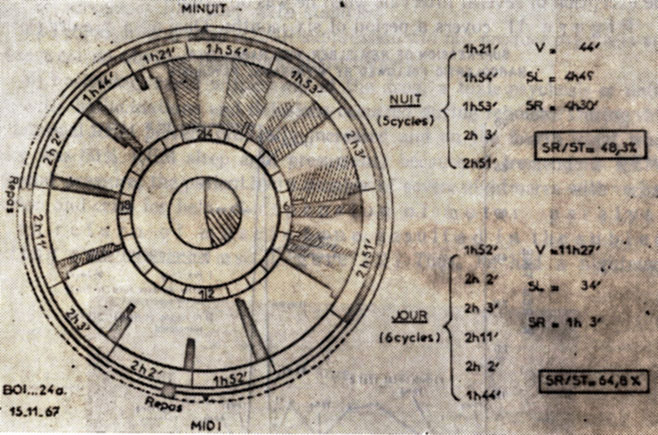

One of the patients to whom I administered Nardil suffered from narcolepsy. A major contribution of research in sleep and dreaming to psychiatry has been the understanding that has been brought to bear on this disease entity. Classical or true narcolepsy consists of a group of four cardinal symptoms: sleep attacks, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations. It can be said to represent essentially a disturbance of REM sleep and all the symptoms can be explained on this basis. Thus, it has been shown 1hat the diurnal sleep attacks are actually attacks of REM sleep associated with dreaming and loss of muscle tone- Further (Figure 10 ) by observing narcoleptics around the clock, sleep attacks have been found to occur in a 90-100 minute cycle. There is considerable evidence that the REM cycle is latently present during the day. In narcolepsy, due to the failure of the waking system to keep it suppressed, the REM cycle manifests itself during the day in the form of sleep attacks.

In cataplectic attacks, the subject under the stress of strong emotion or laughter experiences a sudden marked and total loss of muscle tone and falls down in a heap. It is assumed that these attacks represent the loss of muscle tone concomitant with REM sleep, dissociated from the sleep attack itself, since during cataplexy the subject is awake. One way of looking at the matter is that mind sleep is dissociated from body sleep. The nocturnal sleep of narcoleptics is normal except that the true narcoleptic experiences a sleep onset REM period instead of this occurring an hour to an hour and one-half after sleep onset. During this sleep onset REM period the subject may experience sleep paralysis which is essentially a nocturnal cata- plectic attack and the initial dreaming is experienced as hypnagogic hallucinations.

Figure 13

For many years narcolepsy has been treated with amphetamines but with only partial success and many patients received little or no benefit from this class of drugs, because they are only partial REM suppressors.

Because of the total and prolonged REMP suppression effect of Nardil it occurred to Wyatt and his co-workers to test out the usefulness of this drug in narcolepsy. They treated seven amphetamine-resistant narcoleptics with Nardil with striking reduction in all four types of symptoms- There were several important side effects. Three men had difficulty getting erections during the initial weeks on the drug and two of four females reported difficulty attaining orgasm. Weight gain due to excessive eating has been a consistent problem for six of the patients. No apparent adverse psychologic effects resulted from total REM suppression carried out as long as a year- None of the patients remembered dreaming in the morning, suggesting that it was abolished along with the REM periods, and none indicated that the loss of dreaming was in any way detrimental.

My patient was a 58 year old man who had suffered from sleep attacks for 40 years. (He was first studied by Dement and myself some ten years ago and was probably the first narcoleptic investigated in a modern sleep laboratory.) He was constantly fired from jobs because of falling asleep, in spite of the fact that he was on heavy doses of amphetamines. Additionally, he had quite frequent attacks of cataplexy triggered by his telling aggressive jokes or making a hostile remark.

In the laboratory he showed erections associated with the REM periods but less than normal frequency and amplitude, probably due to his age. He was a profuse dreamer, remembering very long and detailed dreams. He was recorded continuously during one 24 hour period and found to have four REM periods during the night and five additional ones during the day with an average cycle length of 105 minutes, approximately the normal length.

The patient was put on Nardil with doses up to 75 or 90A mg daily and over a period of nine months showed a total suppression of REM sleep with the exception of several intervals when he was off drug.

Figure 11 covers a period of six months. During a pre-drug period about two months before the events shown in the slide, subject was given a battery of psychological tests including Rorschach, TAT, Bender Gestalt, Figure Drawing and WAIS. The slide indicates that the same tests were given for a second time following a 26 day period of near total REM suppression. An interval of little more than two months separated the first and second tests. During the next three months the patient showed marked REM suppression and the following findings:

1) We were able to bring about a near complete disappearance of both h is cataplexy and narcoleptic attacks.

2) The side effects of Nardil were very well controlled with the exception of a marked diminution of sexual activity and desire. Although he had been having frequent intercourse prior to treatment, while on drug he developed total erectile and ejaculatory impotence. Additionally, strain gauge recordings indicated that nocturnal REMP erections practically disappeared. Unlike Wyatt's subjects, both of ours failed to show increased eating and weight gain.

3) Since the patient had frequent spontaneous awakenings from sleep during the period of total REMP suppression we were able to interview him for mental content. There was no evidence of dreaming and no indication that the content of NREM awakenings was more dreamlike. The reports obtained were either of brief thoughtlike content or isolated images. For example the patient woke with the thought, "I am the murderer" or the single word "monthly" or the melody of a song. He had images such as the following: "A box of tacks fell into a box of strawberries" or "I was gluing Sominex pills on envelopes like they were stamps".

4) Prolonged and total REMP suppression did not produce psychosis and there were no obvious behavioral disturbances.

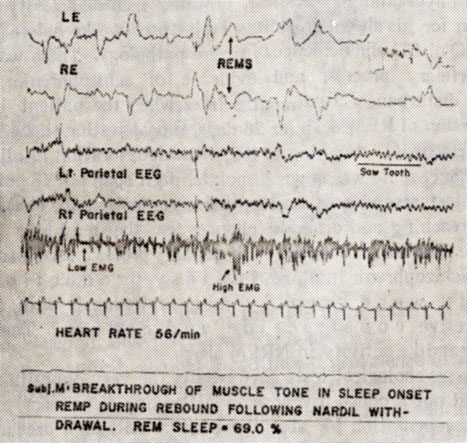

5) Following rapid withdrawal of the drug, a toxic psychosis or delirium with hallucinations and delusions occurred during rebound. During drug withdrawal REM percent gradually increased and on the fourth night when there was 60% REM sleep and, presumably because of tremendous REMP rebound pressure, the patient had a number of severe nightmares with verbalization and cries for help. Suspension of motor paralysis with return of muscle tone resulted in the subject acting out his dreams. (Figure 12) Thus, he had a nightmare about his brother pushing him out of the car and felt himself repeatedly falling. He was found lying on the floor and said that he had fallen out of bed five times, the number of times his brother had pushed him out of the car. The following day, the patient was given his third battery of tests and that night REM sleep reached a level of 69%. At the beginning of the sleep period he bacame disturbed, obviously entering into a drug withdrawal delirium. For more than an hour he had brief periods of REM sleep with hallucinations alternating with attacks of cataplexy. Clearly, dreaming had intruded or spilled over into the waking state, the motor barrier was breached and the patient was acting out his dreams. The patient made running movements, actually got up and tried to open the door, gestured and pointed and these movements were temporally associated with dream content. The next day he was sitting on a couch when, he dreamed that he saw a clarinet lying on the floor in front of him. He got up to get it (actually he did get up) when an attendant tried to restrain him and the patient became violent and attacked him. He appeared to be hallucinating. Following this episode and in order to terminate the developing delirium, the patient was given 75 mg Nardil. That night REM sleep declined to 51%, within five days reached zero, where it has remained, and psychotic symptoms quickly disappeared.

6) Although, during interviews, the patient denied drug was having any effect, there were obvious personality changes. Before Nardil, he was eccentric, garrulous, witty, schizoid, hypomanic and highly intelligent, while on drug he was subdued, somewhat depressed, less talkative, lively, imaginative or humorous - a much duller personality. He insisted that memory, problem solving ability, concentration, etc. had not altered and reported no increase in daydreaming, fantasies, or other mental activity indicative of

compensation for his absent dreaming. Tests three weeks before Nardil showed a full scale IQ of 133 and evidence of severe pathology. There was a flooding of primary process, and evidence of schizophrenic mechanisms and thought disturbance. Two months later when the patient had sustained total suppression of REM sleep for 26 days, repeat testing showed marked cognitive impairment,IQ dropping to 122, with deterioration in all cognitive areas. Performance scale was down 15 points, digit span fell 18 points, block design 27, (object assembly 16, perceptual organization 16, etc.) Rorschach indicated far-reaching and dramatic changes for the better in the emotional sphere. Instead of flooding with primary process, secondary process predominated: schizophrenic thinking, fantasy production and impulsivity were greatly diminished, with, however, increased affective constriction and control. There was no increase in dreamlike activity in NREM sleep.

Thus, psychological tests gave results the very opposite of those predicted. It did not produce psychosis or a flooding of primary process during the day in compensation for absent dreaming. Although dreaming does not appear to be a necessary psychological process, caution must be exercised in concluding that no harmful effects result from total suppression of REM sleep and dreaming. There was marked cognitive deterioration, the patient be- came duller and more constricted emotionally with less capacity for fantasy. The hallucinations and primary process thinking associated with the dream may be necessary for imaginative and creative fantasy, for preservation of cognitive excellence and a number of qualities the loss of which may make us less human.

However, these suggestions must be viewed with considerable reservation since it is difficult to decide whether the cognitive and affective changes and the decrease in primary process thinking were due to the effects of Nardil or to the REMP suppression, brought about by the drug.

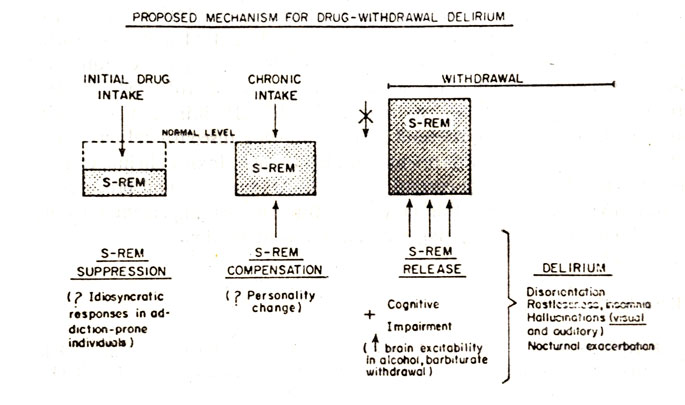

8) Although total REM suppression does not appear to cause psychosis, psychosis can come about during the rebound following rapid withdrawal of Nardil and following withdrawal of other REM suppressing drugs such as alcohol and barbiturates providing the rebound is great enough - the threshold for REM intrusion into the waking state appears to be the point at which REM sleep reaches a level of 60% or more of total sleep time. When this occurs, motor paralysis is breached, muscle tone is regained and dreams are acted out. Thus, the so-called REM intrusion or spill-over theory of drug withdrawal psychosis or acute delirium first proposed by Dement and myself, and elaborated by Gross et al., Greenberg and Pearlman and Feinbarg and Evarts, is supported (Figure 13).

9) Finally, it is of great interest that the third battery of tests, given at the height of rebound, and just about ten hours before psychotic symptoms were to become manifest, showed a continued prevalence of secondary processes and not the flooding of primary process that was present before drug administration. There was even less fantasy production, and more ideational constriction than on the second test given during total REMP suppression. However, there was some indication of impending catastrophe. The test showed less defensive flexibility and restitutive capacities as compared to the second test, suggesting a probable course of decompensation. It would appear that in spite of the tremendously increased REMP pressure, defensive and controlling agencies in the mental apparatus prevented a breakthrough of REMP until some threshold was reached when a veritable flooding occurred - this was the point of psychosis.

I want to summarize by emphasizing two points. First, the therapeutic results on night terrors by means of a drug that suppresses Stage 4 and the reported improvement in depression and suppression of symptoms of narcolepsy by administering Nardil, have important implications for the mind-body problem. They indicate that by suppressing a physiological state such as Stage 4 or REM sleep it is possible to suppress the psychological events that normally accompany such states or abnormal symptoms such as night terrors, that occur during them.

Second, I hope I have made clear the distinction between the events during total prolonged REMP suppression and the events associated with rebound. The notion that during the former REMP pressure develops resulting in increased compensatory dreamlike activity, possibly producing psychosis, has turned out to be false. Something quite different appears to take place, that is, while REMP suppression is ongoing there is a disruption of those cognitive processes having to do with dream formation and quite possibly a disruption of certain aspects of waking mentation: namely, those imaginative, fantasy and "creative" types of thinking that may utilize primary process. Rather than these processes being enhanced they are diminished and this may represent the chief deleterious consequences of prolonged REMP suppression. On the other hand, as noted, the REMP intrusion or spillover mode is valid during the rebound period following discontinuation of REMP suppressing drugs and if this rebound is high enough, toxic delirium or psychosis may supervene. In our current drug culture these rebound processes need further investigation and this may constitute another important area where research on sleep and dreaming may make a contribution.

References

1. Akindale, M. O., Evans, J. I. and Oswald, I. Monoamine oxidase inhibiters, sleep and mood. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol., 29: 47-56, 1970.

2. Arkin, A. M., Antrobus, J. S., Toth, M. and Sanders, K. The effects of REMP deprivation on sleep mentation. APSS, 1972.

3. Dement, W. C. The biological role of REM sleep (circa 1968). In: Sleep: Physiology and Pathology. A Symposium, ed: Kales, A., Phila, J. B. Lippincott. 245-265, 1969.

4. Dement, W. and Fisher, C. Experimental interference with the sleep cycle. Сanad. Psусhiatr. Assn. J., 8: 395-400, 1963.

5. Feinberg, I. and Evarts, E. V. Some implications of sleep research for psychiatry. Pro с. Amer. Psychopath. Assn. 58: 334-393, 1969.

6. Fisher, С., Gross, J. and Zuch, J. A cycle of penile erection synchronous with dreaming (REM) sleep. Arch. Gen. Psyсhiat., 12:29-45,1965.

7. Greenberg, R. and Pearlman, C. Delirium tremens and dreaming. Am. J. Psychiatry., 124: 37-46, 1967.

8. Gross, M. M. and Goodenough, D. R. Sleep disturbances in the acute alcoholic psychoses. Psyсhiat. Res. Rep. Amer. Psyсhiat. Assn., 24: 132-147, 1968.

9. Ohlmeyer, P., Brilmayer, H., Hullstrung, H. Erections during sleep. Pfluger's Arch. f. d. ges. Physiol., 248:559, 1944.

10. Oswald, I. Human brain protein, drugs and dreams. Nature, 223: 893-897, 1969.

11. Vogel, G. W. REM Deprivation: III. Dreaming and Psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 18: 312-329, 1968.

12. Wyatt, R. J., Fram, D. H., Buchbinder, R. and Snyder, F. Treatment of intractable narcolepsy with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. New Eng. J. Med., 285: 987-991, 1971.

13. Wyatt, R. J., Fram, D. H., Kupfer, D. J. et al. Total prolonged drug-induced REM sleep suppression in anxious-depressed patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 24: 145-155, 1971.

|

ПОИСК:

|

© PSYCHOLOGYLIB.RU, 2001-2021

При копировании материалов проекта обязательно ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://psychologylib.ru/ 'Библиотека по психологии'

При копировании материалов проекта обязательно ставить активную ссылку на страницу источник:

http://psychologylib.ru/ 'Библиотека по психологии'